SYNOPSIS

Director Amr Bayoumi remembers that he documented the journey of the statue of Ramses II with his personal camera in 2006. The journey was from Ramses square, one of the largest squares in Cairo, to his new place in the Grand Egyptian Museum. It was the biggest transfer process Cairo streets ever witnessed, a journey that took over 12 hours in the charming Cairo atmosphere.

Amr is inspired by this journey to tell his story with the statue since childhood as his house was a few steps from Ramses square and his personal relation with his father who was a symbol of superior authority in his youth.

Watch trailer

Notable Awards and Acknowledgements

Official Selection DOK Leipzig,

Best Feature Documentary Award at the 21th Ismailia International Film Festival

Film title: Where did Rameses go?

Director: Amr Bayoumi

Year: 2019

Country of production: Egypt

Genre: Documentary

Rating: G

Language: Arabic

Subtitles: English

Duration: 62 minutes

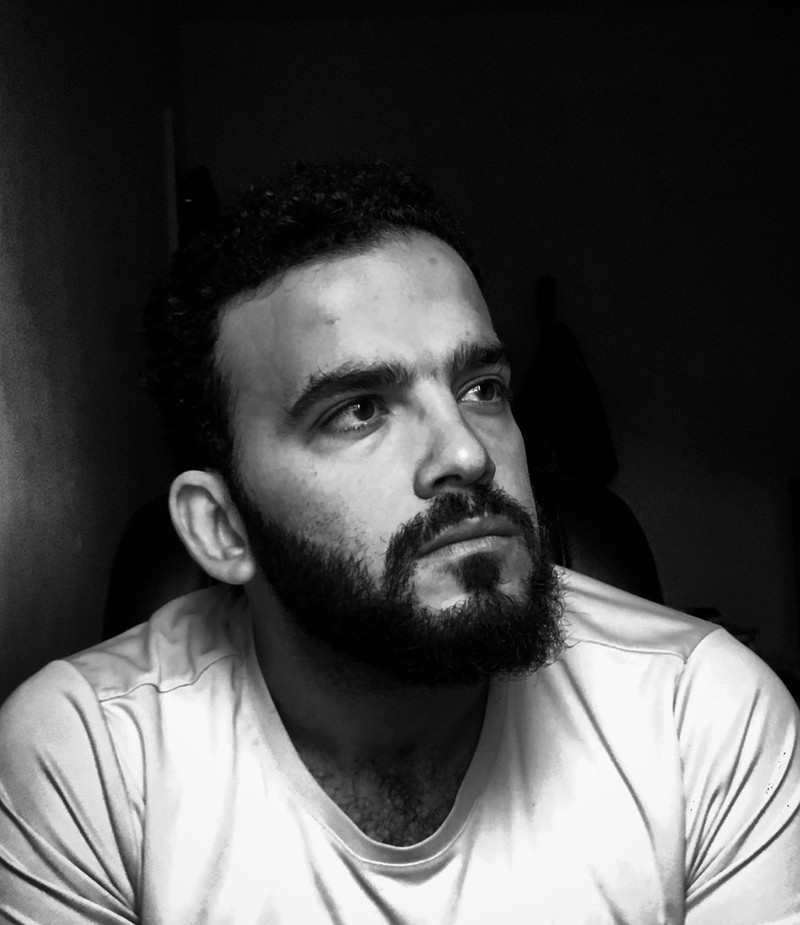

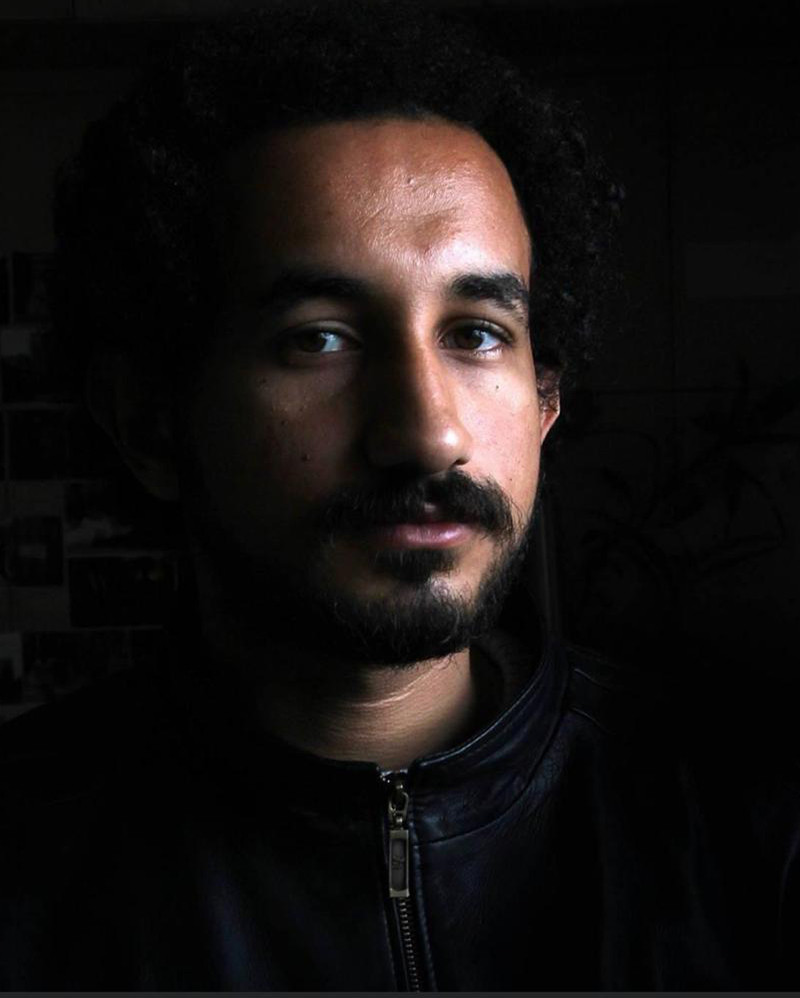

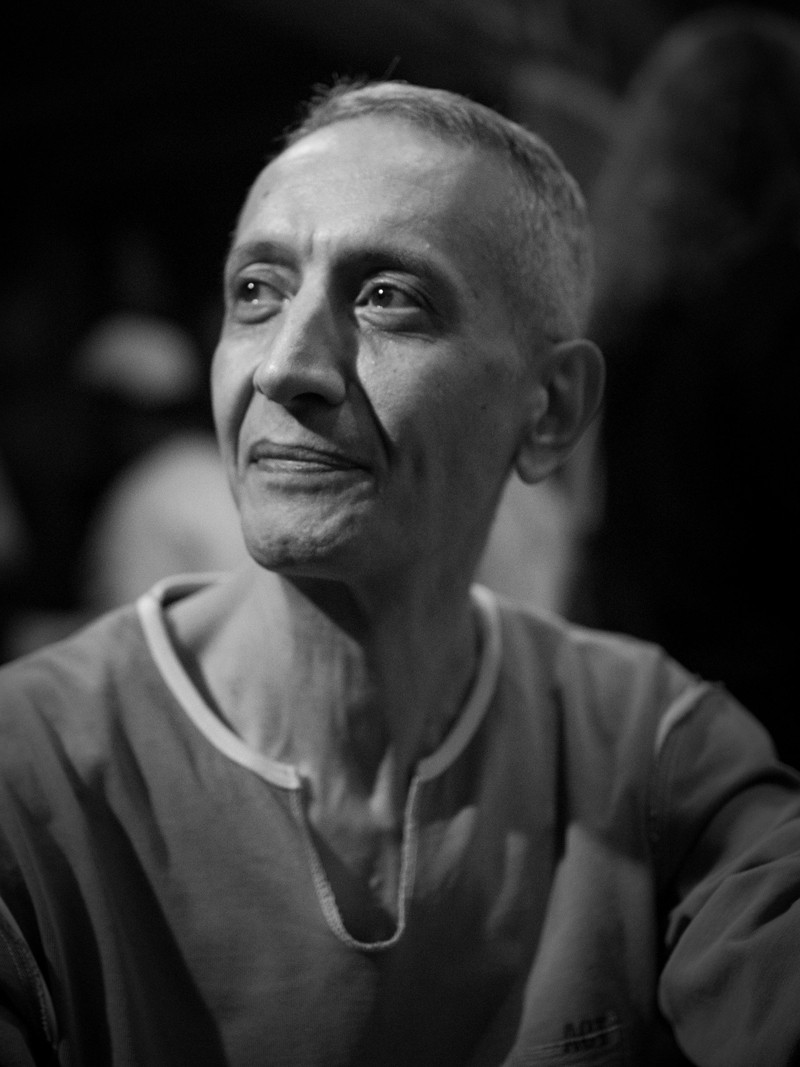

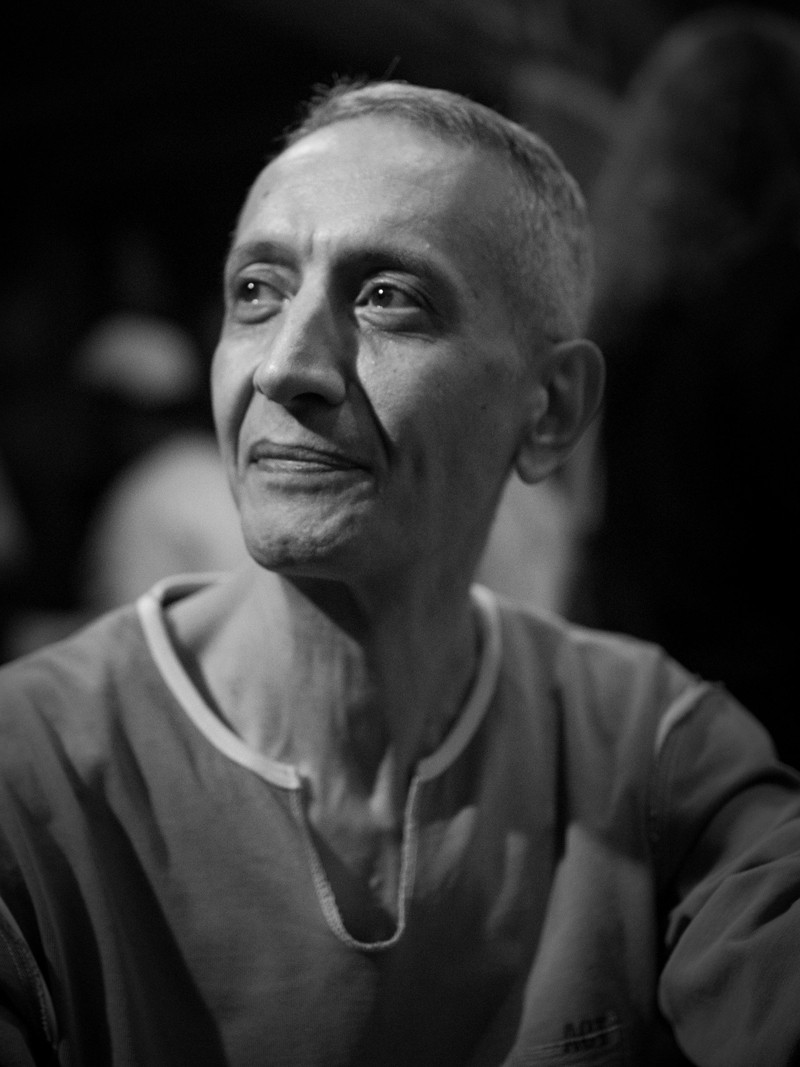

AMR BAYOUMI

An Egyptian independent Scriptwriter and Film Director with an exceptional exposure in a diversity of media and film industry related fields spanning through 35 years of experience. Amr holds a Bachelor degree of Art in Film Direction-from the prestigious Higher Cinema Institute in Cairo, Egypt 1985 and was the recipient of multiple awards for his work namely Al-Jesr (The Bridge) 1999; a movie that delicately captures the communication gap in a middle class Egyptian family across three different generations and starred by the likes of Mahmoud Morsi and Madeleine Tabar. Most recently his long documentary Ramses Rah Fin (Where did Ramses go) 2019 received the grand prize of Ismailia Film Festival for managing to link a complex personal history to the history of an entire country, documenting an extraordinary event.

Amr started his career (prior to his graduation) as an assistant director working alongside a number of critically acclaimed Egyptian movie directors where he took part in the realisation of 10 long feature films between 1984 and 1988 after which point he has moved to the United Kingdom and worked in London between 1988 and 1994 as a film critic for the Al-Arab Newspaper as well as a Projection Manager and Publicity Manager for United Cinemas International and Cannon Cinemas Limited. This has given him further exposure in his industry and valuable insights that he continued to leverage throughout his career.

Upon his return to Egypt in 1995 he dedicated his efforts to work on films that addresses social challenges in an ever changing social dynamics including Balad El Banat (Girls Country); a film that follows the journey of four girls moving from the leafy countryside to the hussle and bussle of Cairo and the internal conflict that comes with reconciling the country simplicity with the harshness of the city.

Amr further stretched the envelope by researching, writing, producing and directing a bold documentary named Kalam Fel Genss (Sex Talk) where he ventured into the unchartered territory that is sexual health in the Egyptian society and unveiled the harsh reality of FGM (Female Genital Mutilation) amongst other themes in such topic.

Lately Amr has been focusing on documentaries, including a number of productions with Al-Jazeera where he directed a series of documentaries touching on Bosnia Post War Society, Crime Against Humanity as well as interacting with the latest social and political changes in Egypt.

Awards:

Bronze Award, Cairo International Film Festival for Children, “Al-Gisr”

Best Direction, Egyptian National Film Festival, “Al-Gisr”

Jury’s Special Award, Egyptian Catholic Centre For Cinema, “Al-Gisr

Grand Prize Award, Ismailia International Film Festival, “Ramses Rah Fin”

Honorary Positions:

Board Member of Cadre Foundation for Audio Visual Art-(NGO) 2005-2006

Board Member of The Independent Syndicate for Film Makers 2014 - 2018

AMR BAYOUMI